In their forthcoming article Defining the Scope of ‘Possession, Custody, or Control’ for Privacy Issues and the Cloud Act, the authors provide the first full analysis of the scope of “possession, custody, or control” under the Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (Cloud Act). The text of the paper is available on SSRN, and will be published in full by the Journal of National Security Law & Policy. The introduction is presented here:

When the U.S. entered into its first Mutual Legal Assistance Treaty (MLAT) with Switzerland in 1977, it was in response to law enforcement being frustrated with knowing the location of evidence and being unable to reach it.[1] At that time, criminal organizations were taking advantage of Swiss banking secrecy laws to hide money and transactions, frustrating U.S. law enforcement investigations.[2] Over time, more countries entered into MLATs as a means of accessing evidence that had been located but was outside of a country’s physical jurisdiction. Today, however, the sheer amount of electronic evidence has made ubiquitous the need for law enforcement to access this kind of evidence stored outside of their physical jurisdiction. It was in this context that the U.S. Congress passed the Cloud Act in 2018.

When the Cloud Act came into law, it mooted the Microsoft Ireland case then pending in the U.S. Supreme Court, but left stakeholders confused as to the current state of play for accessing electronic evidence stored outside the U.S.[3] The Cloud Act codified that the U.S. government has the power to order the production of electronic evidence from U.S. service providers “regardless of whether such [evidence] is located within or outside of the United States.”[4] Instead of location, the Cloud Act states that the determining factor of whether or not the service provider must provide the evidence specified is whether the evidence is in the provider’s “possession, custody, or control.”[5] Yet, the Act does not define what constitutes “possession, custody, or control” of electronic evidence. This article addresses that task, defining that key term.

Without a clear definition, some stakeholders, particularly in Europe, have understandably raised concerns about the scope of the U.S. government’s asserted authority under the Cloud Act. Member of European Parliament Sophie in ‘t Veld wrote that “[w]ith the CLOUD Act, the American have direct access to European databases with data on European citizens.”[6] The French government has expressed concern that the Cloud Act is harmful to its “digital sovereignty,” and French private sector actors have accused the U.S. government of enabling the U.S. government to engage in economic espionage targeting foreign companies.[7] While some of these concerns misunderstand the Cloud Act’s interaction with existing U.S. law,[8] the lack of clear definition of “possession, custody, or control” has engendered confusion.

Similarly, law enforcement, both inside and outside the U.S., would benefit from a clear understanding of “possession, custody, or control.” First, for cautious investigators an unclear definition means a higher likelihood they will rely on a conservative interpretation of the phrase. Doing so means they may miss out on collecting evidence to which they are entitled, or delaying their access to such evidence by instead relying on a more well-trodden but time-consuming process like a formal MLAT request. Second, more risk-accepting investigators may take an aggressive interpretation of the phrase to collect more evidence than they would otherwise be entitled to demand. Finally, a clearer definition would enable more effective sharing of investigative responsibilities. Both U.S. and foreign law enforcement could cooperate more effectively for joint and parallel investigations, with a clearer understanding of what U.S. law enforcement can and cannot do with its powers as defined under the Cloud Act.

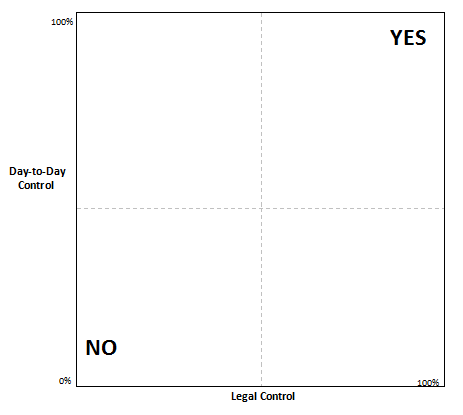

To assist in understanding how courts may analyze whether a company has “possession, custody, or control” over data, we introduce a new visualization tool, shown below as Figure 1.

Fig. 1 – Describing Where Courts Find Possession, Custody, or Control

The graph has two variables: the amount of legal control the entity receiving the legal process has over the evidence, and the amount of day-to-day control the entity exerts over the evidence. Where the entity has 100% legal and day-to-day control of evidence, courts would almost certainly require production of the evidence sought. Likewise, where the entity as 0% legal and day-to-day-to control, courts are unlikely to require production and the government would be required to issue process on an entity that more clearly has “possession, custody, or control” over the evidence sought.

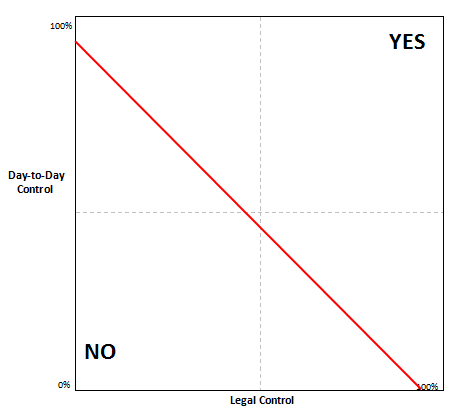

While we do not expect courts to make a precise finding of the percentage of legal and day-to-day control in their opinions, we do suggest that this graph can help conceptualize key aspects of how courts interpret the doctrine. In addition to the two axes of “day-to-day” and “legal” control, one can also add an approximate line of where courts tend to find possession, custody, or control, in some cases even where the evidence is not held within the corporate entity receiving the request. Figure 2 illustrates one such hypothetical line, although we emphasize that we are not trying in this illustration to reach legal conclusions about what percentage of control on each axis leads courts to find possession, custody, or control. In Figure 2, a point up and to the right of the line would result in a decision to find such control, while a point below and to the left of the line would not. The line in Figure 2 describes doctrine in which 100% legal control or 100% factual control would result in requiring production of the information, which is the most likely outcome from the case law we further analyze below.

Fig. 2 – Line Roughly Describing Where Courts Find Possession, Custody, or Control

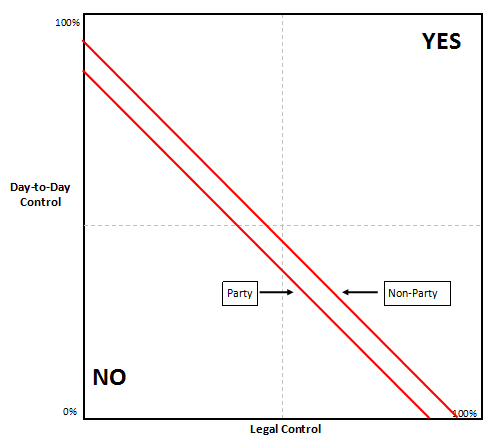

In additional to “day-to-day” and legal control, courts will often look to whether the targeted entity is a party to the case at hand. Generally speaking, courts are more likely to require production from a party to the case, as a party is incentivized to avoid producing evidence that may make it less likely to prevail. Conversely, a non-party has no such direct interest in the case, and therefore has no inherent incentive to avoid production. Figure 3 shows the effect of whether the request is to a party or a non-party: a party is generally required to produce evidence in a greater range of situations than a non-party.

Fig. 3 – Effect of Party and Non-Party for Where Courts Find Possession, Custody, or Control

We suggest that Figure 3 offers a visual, concise summary of our research on where courts require an entity to respond to a government request.

One could imagine applying this graph in two ways. In the first method, a holistic analysis of the particular facts of the individual case would result in two values: the total percentage of legal control and of day-to-day control the entity exerts over the data. Alternatively, for each key fact about the entity’s interaction with the data, one could determine how much legal and day-to-day control that individual fact demonstrates, and plot each fact accordingly. There would then be either one point, or a series of points, plotted on the chart, depending on the method used.

We do wish to stress that the graph is intended as an aid to understanding – we do not intend Figure 3 to portray the precise location of the x and y intercept, or the precise shape or slope of each line. Instead, we aim to use this graph to help illuminate how courts have interpreted the meaning of “control” in the cases we review in the course of this article.

This paper examines the current lack of clarity about the meaning of “possession, custody or control,” and suggests how existing case law interpreting this exact phrase in other legal contexts can inform U.S. judges in interpreting the phrase’s meaning in the Cloud Act. Part II examines whether the use of this standard in the Cloud Act expanded the DOJ’s previous power to require the production of electronic evidence from U.S.-based service providers. This part reviews the Bank of Nova Scotia line of cases and lower court rulings in Microsoft Ireland, as well as the different viewpoints on the scope, prior to the Cloud Act, of the U.S.’s authority to demand the production of electronic evidence stored outside the U.S. Our conclusion, based on this review of prior cases, is that the Cloud Act primarily confirmed the previous judicial interpretations, rather than being the significant expansion of authority that some have claimed.

Part III examines how the phrase “possession, custody, or control” has been interpreted under the Federal Rules of Civil and Criminal Procedure, and how that jurisprudence might inform future challenges of U.S. authority under the Cloud Act. The exact phrase is found in Rules 34 and 45 of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and Rule 16 of the Federal Rules of Criminal Procedure. These rules consider when parties and non-parties to litigation, including the U.S. government, can be required to turn over information and documents. This section will then look closely at four additional implications from existing jurisprudence:

-

- How the courts have treated different types of international corporate structures and how the location and nature of parent, subsidiary, or affiliated corporations affects the determination of “possession, custody, or control;”

- How the interpretation of “possession, custody, or control” differs as applied to parties and non-parties to a specific action, and which more closely resembles the position of an electronic service provider under the Cloud Act;

- How the courts decide if and when to “pierce the corporate veil” for the purposes of asserting “possession, custody, or control” of information, and how to differentiate the legal and policy context of “piercing the veil” in this context as opposed to other corporate contexts; and

- Why an entity’s “control” of data for purposes of the Cloud Act is different from the designation of a “data controller” under the European General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR).

Finally, this part will attempt to synthesize these different interpretations and nuances of “possession, custody, or control,” and how they might apply to the Cloud Act in light of its particular policy implications.

Part IV will review concepts similar to the “possession, custody, or control” standard in other nations. Specifically, this section will review Belgian law, based on prominent recent cases decided by courts in that country. The Belgian courts have required the production of evidence stored by electronic service providers outside of Belgium in two cases, involving Yahoo! and Skype. This section will also compare how the U.S. and Belgian courts have approached when to require the production of evidence in these types of cases, highlighting similarities and differences.

To read the full article, please click here.

These statements are attributable only to the authors, and their publication here does not necessarily reflect the view of the Cross-Border Data Forum or any participating individuals or organizations.

[1] See William W. Park, Legal Policy Conflicts in International Banking, 50 Ohio St. L.J. 1067, 1096 (1989).

[2] See id.

[3] This paper will focus on Sections 103 and 104 of the Cloud Act which mooted the Microsoft Ireland case by amending the Electronic Communications Privacy Act. See Consolidated Appropriations Act of 2018, Pub. L. No. 115-141, Division V Clarifying Lawful Overseas Use of Data Act (2018). For further discussion of multiple legal issues arising under the Cloud Act, see Peter Swire & Jennifer Daskal, Frequently Asked Questions about the U.S. CLOUD Act, Cross-Border Data Forum (Apr. 16, 2019), https://www.crossborderdataforum.org/frequently-asked-questions-about-the-u-s-cloud-act/.

[4] 18 U.S.C. § 2713 (2019).

[5] Id.

[6] See Long arm of American Law? Not in Europe!, Sterk Europa Sophie (Feb. 5, 2019) https://sophieintveld.eu/long-arm-of-american-law-not-in-europe/.

[7] See Justin Hemmings & Nathan Swire, The Cloud Act Is Not a Tool for Theft of Trade Secrets, Lawfare Blog (Apr. 23, 2019) https://www.lawfareblog.com/cloud-act-not-tool-theft-trade-secrets.

[8] See id. (explaining why U.S. normative and diplomatic interests, criminal procedure law, Presidential Policy Directive 28, and the Economic Espionage Act make it highly unlikely that the Cloud Act could be used to conduct economic espionage).