by Karine Bannelier & Anaïs Trotry*

The Cross-Border Data Forum is an official observer to the UN Ad Hoc Committee to Elaborate a Convention on Cybercrime. The following document was submitted to the Committee in connection with the fourth session, beginning in Vienna on January 9, 2023. The document provides information about an important area of discussion for the UN process – what are the definitions of “data”, as evidenced in international legal instruments to date?

Requests for a Definition of “Data” Categories During the UN Convention on Cybercrime Negotiations

During the debate at the UN Ad Hoc Committee, provisions in the convention dedicated to international cooperation were considered by many States to be the most important provisions in the convention along with criminalization. In this regard, a number of questions concerning international cooperation revolved around the issues of electronic evidence sharing, transborder access to data and the protection of personal data. For instance, at the third session, the UN Ad Hoc Committee asked States the following question: “How should the chapter on international cooperation determine the requirements for the protection of personal data for the purposes of the convention?”. While some States underlined the sensitivity of this question, the lack of a common understanding of the different categories of data that could be relevant for the convention and of a definition of “personal data” soon became evident. This situation led some States to ask for agreed definitions on what is meant by data, personal data/non-personal data, content data/non-content data, metadata, subscriber data, traffic data and sensitive data.

Absence of a Definition of Data in the UNTOC and UNCAC

The two UN conventions used as models by the UN Ad Hoc Committee, the UNCAC and the UNTOC, do not provide any definition of data and personal data. The UNTOC does not mention data at all, while the UNCAC mentions the protection of ‘personal data’ (art. 10) but does not define it.

Solutions Provided by Other International Instruments

Some stakeholders took the view that it is essential to keep in mind the evolution of the legal framework surrounding the protection of personal data, which has taken place in many States since the negotiation of the UNTOC and UNCAC conventions, and to include provisions according to which State parties remain free to make cooperation dependent on the recipient ensuring appropriate data protection safeguards. Other States claimed that it would be useful to rely on the solutions provided by the Budapest Convention or other regional instruments such as the African Union Convention on Cybersecurity and Data Protection.

Purpose of the Charts and Methodology

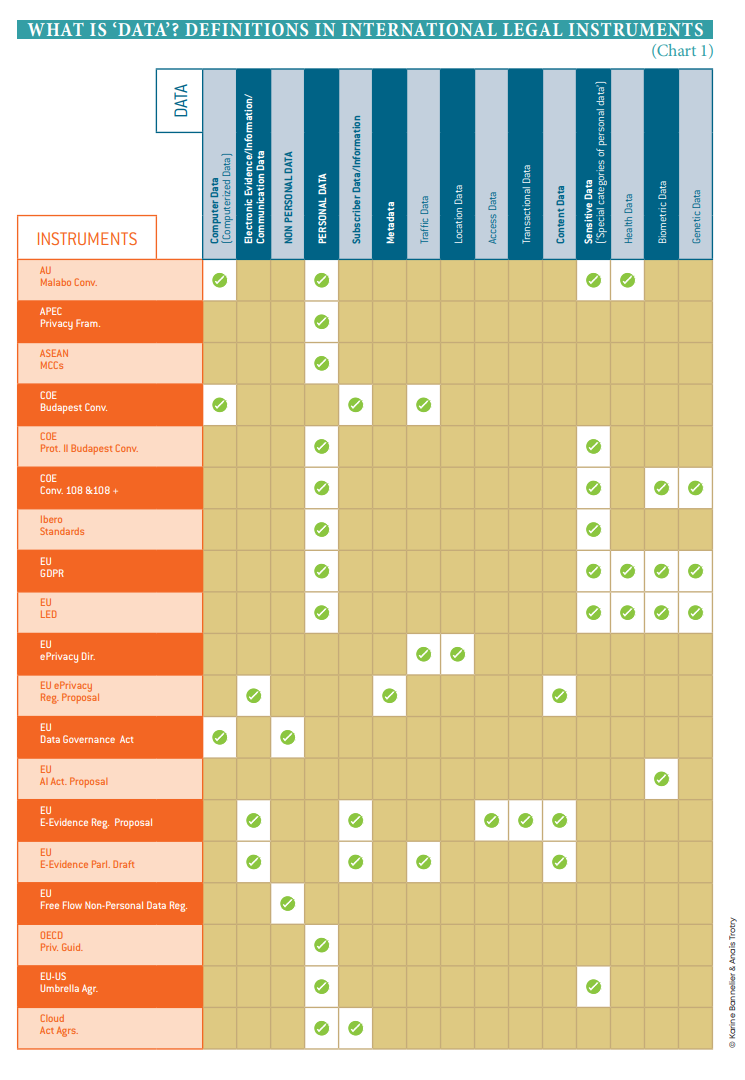

In order to aid the debate on this issue, we have identified, without being exhaustive, the most relevant and important international instruments[1] that provide definitions of the different categories of “data”. We have examined instruments adopted by several international organizations, located on every continent, as well as bilateral instruments such as Mutual Legal Assistance Treaties which, generally, do not include any definitions of “data”, and bilateral agreements on cooperation and exchange of information in the field of law enforcement.

Based on this analysis we have selected definitions that appear in 21 international instruments. Most of these instruments are binding international texts (international treaties, executive agreements, binding acts of international organizations such as EU regulations and directives), but we have also included certain important soft law instruments (from the OECD, the APEC etc.), as well as some texts that have not yet been adopted (such as the EU draft E-Evidence regulation[2] or the European Commission’s proposal for an ePrivacy Regulation[3]) because of their importance.

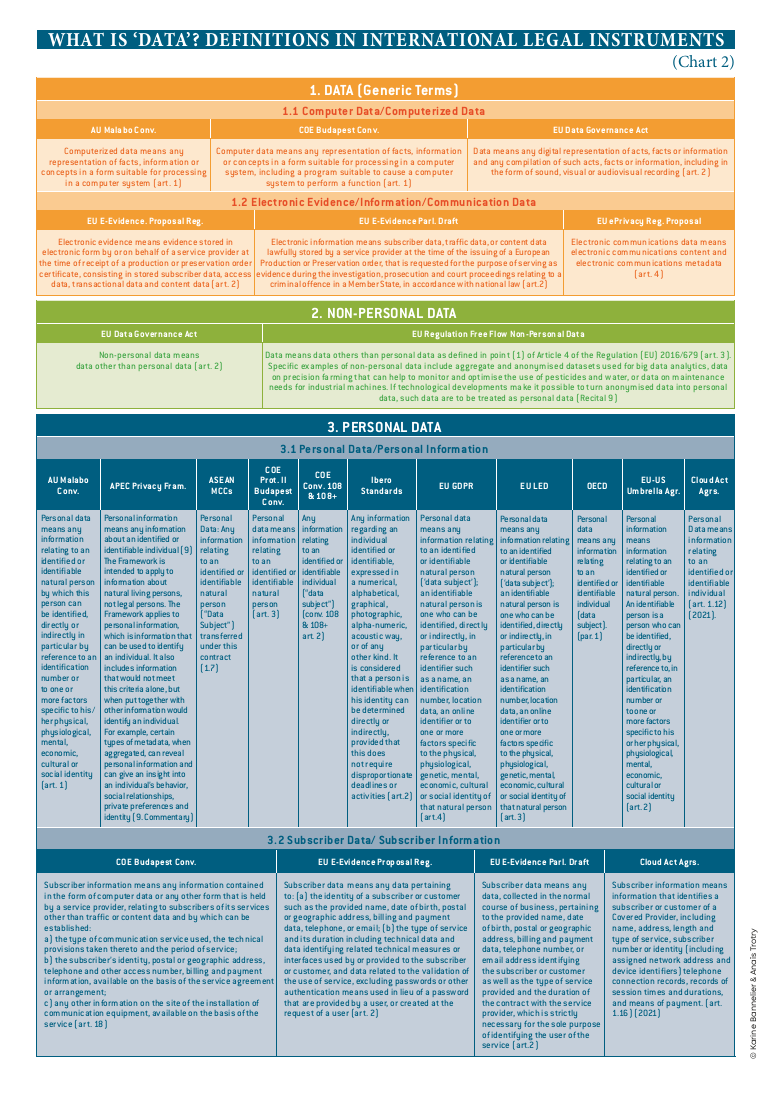

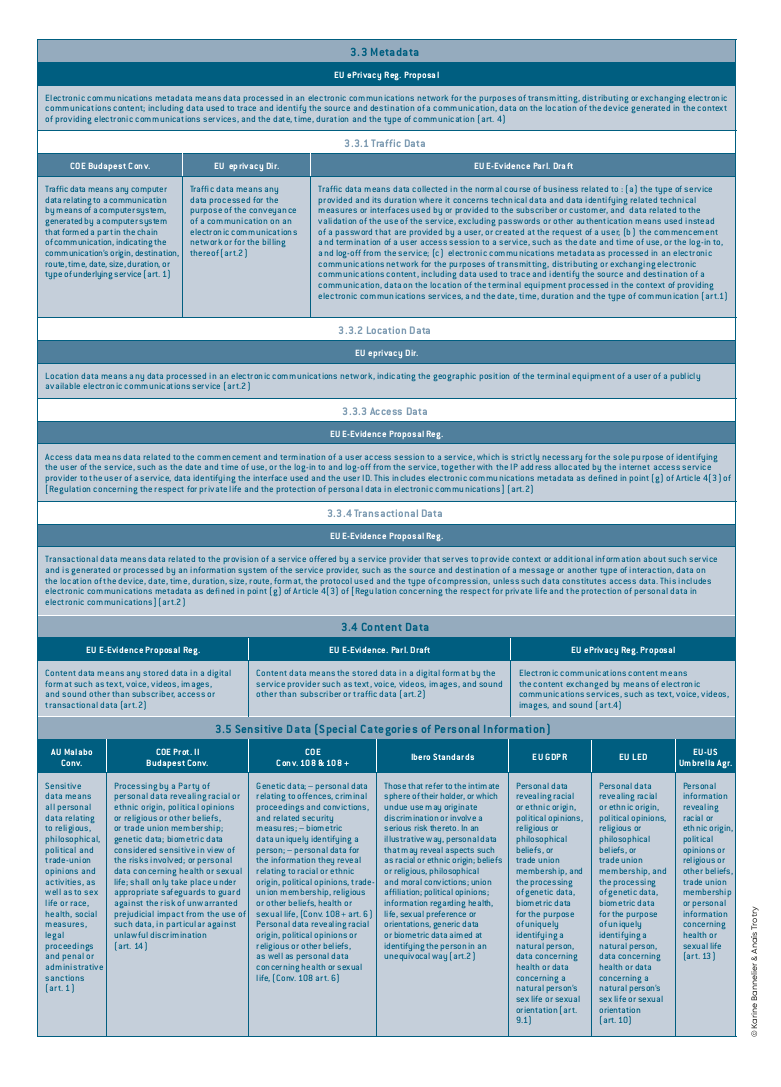

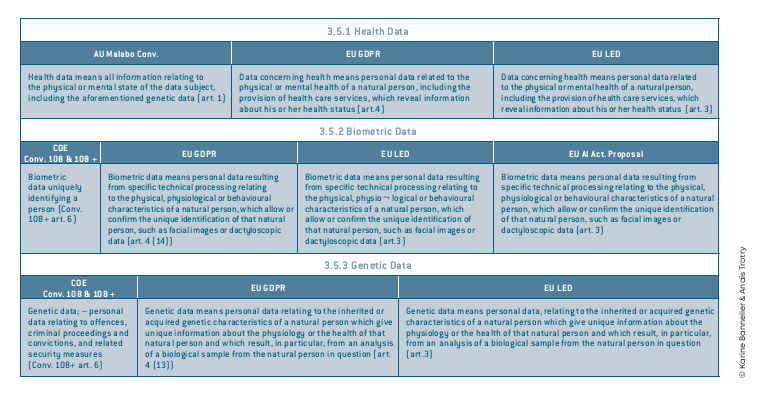

The results of our analysis are presented in two charts. Chart 1 presents how the definitions of the different categories of data variously appear in these 21 international instruments. It also provides details and links for each instrument. Chart 2 compiles the full text of all the relevant definitions, under 3 major headings: 1) “Data – Generic Terms”; 2) “Non-personal data”; 3) “Personal Data” with all their subcategories: Subscriber Data; Metadata (Traffic Data; Location Data; Access Data; Transactional Data); Content Data; Sensitive Data (Health Data; Biometric Data; Genetic Data).

Main Findings and Outstanding Issues

The main findings of this comparative analysis are as follows:

- There is an international consensus about the definition of “personal data”. According to this definition personal data means any information relating to an identified or identifiable natural person by which this person can be identified. This clearly shows, for instance, that information concerning a “legal” (such as a company or a public authority) rather than a “natural” person is not personal data, unless this legal person’s data includes information which reveals the identity of a person (for instance, a specific name and a corporate email address relating to a particular individual, therefore constituting personal data).

- Beyond this consensus, nonetheless, several issues around interpretation remain. This has compelled international bodies, such as the “Article 29 Working Party”, the European Data Protection Board’s predecessor, which unites all European Data Protection Authorities, to issue guidance on how the four constituent elements in the definition of “personal data” found in EU instruments, namely ‘any information’, ‘relating to’, ‘an identified or identifiable’, and ‘natural person’—ought to be interpreted.[4]

- In the field of electronic evidence, regional instruments and bilateral agreements often refer to three main categories of data of interest to law enforcement agencies: subscriber information; traffic/access and transactional data; and content data. These three categories correspond to different legal regimes and thresholds of procedural and substantive protections. The category of “subscriber information” benefits from fewer protections, while the two other categories, considered to be much more intrusive in terms of privacy and human rights, benefit from much greater protections in international instruments. However, researchers have noted that there can be significant spillover across these three categories, and also that the emergence of new services and data types, as well as other factors, might lead to a “re-evaluation of the notion of intrusiveness” and raise questions about whether the existing procedures linked to the categories of data are able to ensure that there are adequate protections and sufficient checks and balances.[5]

- Some personal data (including, but not limited to, biometric, genetic and health data) are considered to be particularly “sensitive”, which has led to the creation of “special categories of data” with a corresponding special legal regime. In general, international instruments prohibit in principle the processing of such categories of data, subject to a series of exceptions.

- The delineation between personal data and non-personal data is of paramount importance in determining the scope of application of several data protection instruments. The category of “non-personal data” is generally defined in a negative way, as including all data which are not “personal”. However, the way in which this is defined does not resolve all of the issues involved. The distinction between “personal” and “non-personal” data can be tricky sometimes, especially when personal and non personal data is mixed together in one dataset or in the context of personal data that have been anonymized, when there is a risk of re-identification.

P.S. The Authors will welcome comments concerning any eventual mistakes inadvertently in the charts or suggestions concerning definitions found in additional international instruments that may be relevant. Please contact as at: karine.bannelier[at]univ-grenoble-alpes.fr.

* Karine Bannelier, Associate Professor in International Law, Director CyberSecurity Institute (University Grenoble Alpes) & Senior Fellow on Cybercrime at the Cross Border Data Forum. Anaïs Trotry, Phd Candidate, Chair Legal and Regulatory Implication of Artificial Intelligence (University Grenoble Alpes).

[1] Our analysis only covers international instruments that reflect agreement between States about these definitions. We have not included definitions of data categories found in domestic laws.

[2] The EU E-Evidence regulation should be adopted in the coming months. Our Charts refer to the draft initially proposed by the European Commission (“EU E-Evidence Reg. Proposal”) in 2018 as well as the draft adopted by the European Parliament in 2020 (“EU E-Evidence Parl. Draft”).

[3] In 2017 the European Commission proposed the adoption of a Regulation concerning the respect for private life and the protection of personal data in electronic communications (“EU ePrivacy Reg. Proposal”) as an alternative to the 2022 ePrivacy Directive. However, this regulation has not yet been adopted and the ePrivacy Directive remains in force.

[4] See Article 29 Working Party, Opinion 04/2007 on the Concept of Personal Data (WP 136) 01248/07/EN, 6.

[5] See Internet and Jurisdiction, “Framing Brief: Categories of Electronic Evidence”, May 31, 2022.

These statements are attributable only to the authors, and their publication here does not necessarily reflect the views of the Cross-Border Data Forum or any participating individuals or organizations.